Born : 1 June 1921, Oradell, New Jersey

Died: 6 Oct 1985, Los Angeles, California

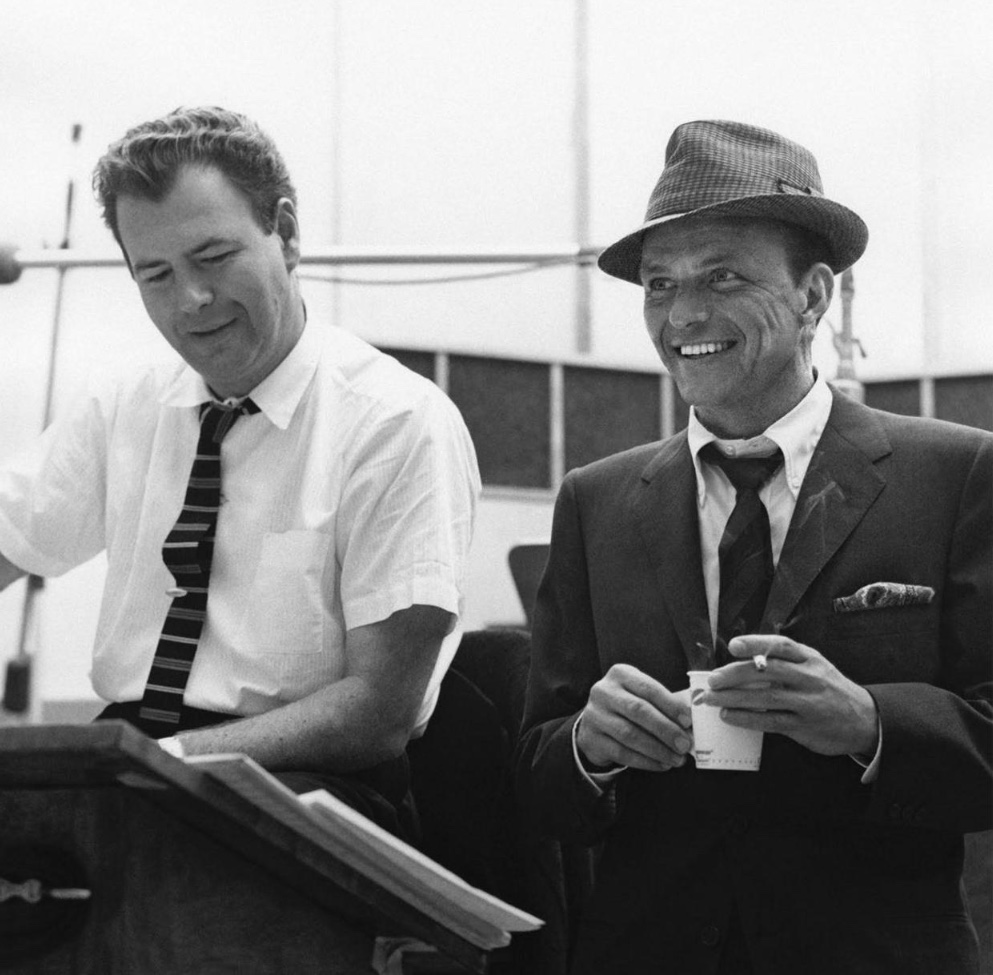

Nelson Riddle 's first arrangement for Frank Sinatra was I'VE GOT THE WORLD ON A STRING. Writing in SESSIONS WITH SINATRA (A Cappella 1999), Charles L. Granata revealed: Sinatra spent more time discussing ideas for recording sessions with Nelson Riddle than with anyone else. Riddle, because of his association with Sinatra from the early years of the Capitol era, was as much responsible for the development of the "concept album" format as anyone.

His and Sinatra's intense pre-studio planning shaped the character of each album as much as the actual sessions themselves.

According to Sinatra, Nelson Riddle was the ultimate musical secretary. "Nelson is the greatest arranger in the world, a very clever musician," Sinatra told Robin Douglas-Home. "He's like a tranquilizer--calm, slightly aloof. There's a great depth somehow to the music he creates. And he's got a sort of stenographer's brain. If I say to him at a planning meeting, 'Make the eighth bar sound like Brahms,' he'll make a cryptic little note on the side of some scrappy music sheet and, sure enough, when we come to the session, the eighth bar will be Brahms. If I say, 'Make like Puccini,' Nelson will make exactly the same little note, and that eighth bar will be Puccini all right, and the roof will lift off!"

Riddle once described his systematic approach to scoring a Sinatra record: "In working out arrangements for Frank, I suppose I stuck to two main rules. First, find the peak of the song and build the whole arrangement to that peak, pacing it as he paces himself vocally. Second, when he's moving, get the hell out of his way. When he's doing nothing, move in fast and establish something. After all, what arranger in the world would try to fight against Sinatra's voice? Give the singer room to breathe. When the singer rests, then there's a chance to write a fill that might be heard.

"Most of our best numbers were in what I call the tempo of the heartbeat. That's the tempo that strikes people easiest because, without their knowing it, they are moving to that pace all their waking hours. Music to me is sex--it's all tied up somehow, and the rhythm of sex is the heartbeat. I usually try to avoid scoring a song with a climax at the end. Better to build about two-thirds of the way through, and then fade to a surprise ending. More subtle. I don't really like to finish by blowing and beating in top gear."

Riddle's daughter, Rosemary Riddle-Acerra: "I think his music was a strong outlet for my Dad's sense of humor. Julie Andrews used to call him 'Eeyore,' because she always felt he had this sadness, this somberness about him. But his music was a whimsical kind of way for him to communicate his humor. He would almost hold back, in terms of dealing with people, and blowing his own horn. But music was a safe outlet for all this, and it was where he felt safe. Through his music, he could communicate the freedom he didn't have in relationships, or in real life."

Riddle worked quickly, and usually--because of the demand for his work on records, in films, and on television--under tremendous pressure. A beautiful, glass-enclosed gazebo of Oriental design (located behind his home) with a million-dollar view of the Malibu surf served as the setting for Riddle's painstaking orchestrations of some of the best-loved recordings in the history of popular music.

"Dad was very businesslike about his work," says Chris Riddle. "His pencils, Eberhard-Faber Blackwing #602s, were laid out, and he always had an electric pencil sharpener at hand. He was very organized He had stacks of long score paper, which a special place over on Highland would make up for him, with his name printed at the bottom. There was a Steinway out there, and a record player. ... He had this table that was like an artist's table, that he liked to work at. The gazebo was a big room, enclosed with thick plate glass windows, and the view of the ocean was framed by eucalyptus trees--it was gorgeous!"

Riddle avoided repetition and "familiar" music lines in favor of his own clever melodies and counter-melodies. "I would do that for several reasons," he explained. "You have the first say in an arrangement, because most singers require an introduction, so you have the first say as far as setting the mood. If you can find something within that introduction that has mileage on it, you can use it in certain breaks in the melody later on. That keeps it interesting. Also, it gives the overall orchestration a subtle cohesiveness which nevertheless is felt, so it seems to be a particular arrangement written especially for this song, whatever the song is. It keeps you occupied, it keeps you interested in what you do."

Sinatra understood and appreciated Riddle's genius. "Though Frank never really learned how to read music, much less play an instrument, he is a man attracted to all the arts, especially classical music. When writing arrangements for him, I could often indulge myself in flights of neo-classical imagery, especially introductions and endings. If he feels I have caught the right mood in the introduction I have written, he is quick to acknowledge it."

Riddle was a master at creating inspired musical fills that floated buoyantly atop a soft bed of feathery-light sustained strings, deftly arranged to contrast with Sinatra's vocal lines. His charts are packed with complex rhythms and subtle melodic motifs which, bit by bit, create a strong underpinning that expertly accentuates and supports a vocal line. Comfortable with nearly any tempo or style, Riddle had a knack for painting backdrops that were richly layered in texture and tone, cushioned enough to allow plenty of room for Sinatra to toy with the rhythm of the lyric, yet distinct enough melodically to stand up on their own. His orchestrations were infused with fine gradations of color and strong, purposeful instrumentation.

"Many of the effects and colors I used are obtained by superimposing one instrument on another, or one section over another section," Riddle wrote in his book on arranging. For example, he often paired alto flute with English horn. He also favored the alto flute-muted horn combination. Many of the swing arrangements he made for Sinatra used a blend of four trombones against a baritone saxophone. Often he would fold contrapuntal rhythms and snippets of the primary melody into the framework of the chart which, when skillfully blended into the whole of the arrangement, become almost invisible behind the vocalist and primary instrumental lines. Individual instruments from within a particular section (woodwinds, for example) are first voiced individually, their melodic phrases then repeated and stacked together to achieve a thick underlying base that provides body and strength to the overall melodic structure.

"In a sense, arranging is a similar exercise to 'Theme and Variation,'" Riddle said. "The arranger is given the basic melody, and his ingenuity and skill combine to form an arrangement of the melody. He can slide any number of different backgrounds and treatments under this original melody, as long as he does not hide it or disfigure it with inappropriate or uncomfortable harmonies. Passing tones are used to give a feeling of flowing motion; these passing tones should be most active when the melody is least active."

The "heartbeat" meter previously described by Riddle, in combination with Sinatra's just-ahead-of or just-behind-the-beat syncopation, is the crux of their musicianship, and the most important element of the singer's post-war signature.

From Riddle's book: "Dynamic shadings are a vital part of presenting music effectively. Some of the most effective crescendos I ever incorporated into my arrangements were not achieved by writing dynamic markings or exhorting an orchestra to observe my flailing arm motions. They were accomplished by gradually adding orchestral weight until the desired peak was reached. The same can be said for diminuendo, in which case the orchestra is progressively thinned out until a ppp (very piano, or softly) is accomplished. True dynamics [changes in loudness] in an orchestra are achieved beautifully and naturally by a combination of orchestral texture and lines. When 'peaks and valleys' occur under these conditions, they sound so logical and effortless as to appear perfectly natural, which they are." Nothing makes an orchestration as attractive as the contrasts achieved by close attention to sensible dynamics. "Frank accentuated my awareness of dynamics by exhibiting his own sensitivity in that direction."

Publicly Riddle offered these observations: "At a Sinatra session, the air was usually loaded with electricity. The thoughts that raced through my head were hardly ones to calm the nerves. If he didn't make any reference to the arrangement, chances are it was acceptable. As far as the tempo was concerned, he often set that with a crisp snap of his fingers, or a characteristic hunching of the shoulders. Frank contributed a lot to the orchestral part of his own records, just by leveling a hostile stare at the musicians, with those magnetic blue eyes! The point of this action was to make me, or any other conductor, feel at that exact moment as if he had two left feet, three ears, and one eye. But it was a positive factor that found its way into the record."

Riddle: "My original interest in writing arrangements came because of orchestral colors. I became fascinated with the harmonies and the various effects you could achieve with single instruments or groups of instruments of varying colors. Therefore, I'm always fascinated by large groups, and I find that small groups are more demanding in a way because you have less to work with."

Riddle last recorded with Sinatra March 14, 1977.

Nelson Riddle was one of the most admired and versatile arranger/composers of the post-war era, with major radio, television, film, and recording successes to his credit. Inspired by his father's amateur band, he learned piano and trombone and joined Charlie Spivak's orchestra after graduating from high school. Over the next few years, he moved on to work with Bob Crosby and Tommy Dorsey's bands, first as a musician and then doubling as an occasional arranger.

After serving in the Army during World War II, he hired on with NBC Radio as a staff arranger.

In 1949, Les Baxter hired him to write some arrangements for a Nat King Cole album. Although Riddle wrote them, Baxter took credit for the highly successful arrangements of "Too Young" and "Mona Lisa"--even Baxter's obituaries attribute them to him. Cole hired Riddle as his lead arranger, and they worked together on over 15 Capitol LPs over the next 10 years. In the early 1950s, Capitol also signed Riddle as an independent artist.

Riddle was known as one of the best arranger for singers, and backed many of Capitol's vocalists, including Margaret Whiting, Dean Martin, Peggy Lee, and Frank Sinatra on his swinging albums ("Songs for Swingin' Lovers," "A Swingin' Affair," "Sinatra's Swing Session") and others. Sinatra said, "Nelson had a fresh approach to orchestration and I made myself fit into what he was doing." Many consider these albums each man's best work. Riddle's own recordings from this period aimed for the same audience as Jackie Gleason, and other "mood music" artists, with titles like "Love Tide," "Sea of Dreams," and "Hey, Let Yourself Go."

His biggest hits, though, were lighter pieces. Riddle had a knack for making his point through understatement that eluded Gleason. The first, "Lisbon Antigua," was brought to his attention by the sister of Nat "King" Cole's manager, and came out at the height of the wave of European covers. His recordings never quite brought Riddle the success he was looking for, though. His earnings as an arranger paled compared to Henry Mancini's royalties from originals like "Moon River" and "Days of Wine and Roses," and Riddle felt something of a rivalry with Mancini throughout their careers.

Riddle also wrote for a number of television shows, including "The Untouchables," and his theme for the series, "Route 66," was released as a single and made it into the Top 40 in 1962. He also scored a number of films, including the Rat Pack classics "Ocean's Eleven" and "Robin and the Seven Hoods," as well as "Harlow," "Red Line 7000," "The Maltese Bippy," "Lolita," "Batman," "A Rage to Live," and "El Dorado." Although Neal Hefti wrote the hit theme for "Batman," Riddle wrote the "zow"-ey arrangements for the actual episodes.

He served as musical director of "The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour" and later, "The Julie Andrews Show." He retired in the mid-1970s, but came back when asked to arrange some songs for an album of torch songs Linda Ronstadt was recording. Riddle commented that he didn't do songs, he did albums, and Ronstadt's producer hired him for the whole album. Riddle's lush arrangements on Ronstadt's "What's New," "Lush Life," and "For Sentimental Reasons" gave the recordings a tremendous boost and helped reintroduce the style that Harry Connick, Jr. and others subsequently imitated to great success. Riddle also arranged and conducted for the inauguration balls for John Kennedy and Ronald Reagan.

Recordings

Soundtrack albums

Email: spaceagepop@earthlink.net