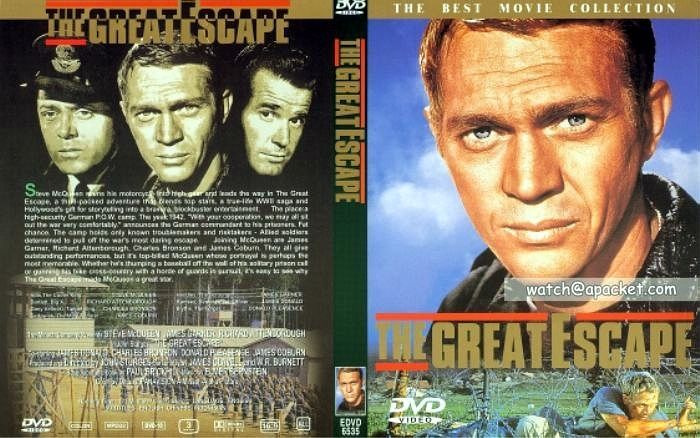

(1963)

Directed by: John Sturges

Written by: James Clavell and W.R. Burnett

| Capt. Virgil Hilts (The Cooler King) | Steve McQueen |

| Lt. Bob Hendley (The Scrounger) | James Garner |

| Squadron Leader Roger Bartlett (Big X) | Richard Attenborough |

| Group Captain Rupert Ramsey (The SBO) | James Donald |

| Lt. Danny Velinski (Tunnel King) | Charles Bronson |

| Colin Blythe (The Forger) | Donald Pleasence |

| Louis Sedgwick (The Manufacturer) | James Coburn |

| Von Luger (The Kommandant) | Hannes Messemer |

| Eric Ashley-Pitt (Dispersal) | David McCallum |

| Flight Ltd. Sandy MacDonald (Intelligence) | Gordon Jackson |

| Lt. William Dix (Tunnel King) | John Leyton |

| Flying Officer Archibald Ives (The Mole) | Angus Lennie |

| Dennis Cavendish (The Surveyor) | Nigel Stock |

| Werner (The Ferret) | Robert Graf |

| Goff | Judd Taylor |

| Kuhn | Hans Reiser |

| Strachwitz | Harry Riebauer |

| Soren (Security) | William Russell |

| Posen | Robert Freitag |

| Preissen | Ulrich Beiger |

| Dietrich | George Mikell |

| Haynes | Lawrence Montaigne |

| Griff (The Taylor) | Robert Desmond |

| Frick | Til Kiwe |

| Kramer | Heinz Weiss |

| Nimmo | Tom Adams |

| Steinach | Karl-Otto Alberty |

| Capt. Felson (Von Luger's Adjutant) | |

| Herr Gundt (Gestapo) |

The following information is compiled from the DVD liner notes and the 23-minute documentary on the DVD.

Paul Brickhill, who wrote the book from which the film is based, was piloting a Spitfire aircraft that was shot down over Tunisia in March 1943. He was taken to Stalag Luft III in Germany, where he assisted in the escape preparations.

P.O.W.s received many seemingly useless items from a charitable group called American Ladies for the Support of Our Prisoners of War. Soon, however, the prisoners realized that the objects contained radio parts and German currency -- vital to the escape attempts.

Red Cross packages often provided prisoners with chocolate and other delicacies that their German captors did not have, giving the prisoners valuable currency to trade for tools needed in their escape.

Approximately five million Germans were assigned to search for the escaped P.O.W.'s, and many thousands were on the job full time for weeks, redirecting valuable manpower from the Nazi war effort, especially important as D-Day approached.

Director John Sturges read Brickhill's book in 1950 and saw the possibilities for an epic film adventure. Not everyone shared his enthusiasm, however. Sturges, under contract to MGM, tried to interest studio chief Louis B. Mayer in the property, but was quickly turned down.

"What's so great about an escape where only three people get away" was a common refrain. The lack of a female romantic interest was also seen as a drawback, and only after Sturges scored a major success with THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN did he have the power to get his dream project produced. But a major challenge still lay ahead: finding a leading man.

Sturges had helped make Steve McQueen a star with THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN, but the actor was reluctant to take the role of "Cooler King" Hilts. McQueen's two previous films had been World War II stories, and both had generated disappointing returns at the box office. Sturges persisted, and after McQueen read an early script draft, the actor agreed to join the cast with one stipulation: McQueen, a motorcycle enthusiast, wanted his character to escape by motorbike at the end of the film. Sturges relented and had the script rewritten to include what would be THE GREAT ESCAPE'S most famous sequence. Six writers worked on the script which went through 11 versions.

After principal photography concluded, Elmer Bernstein composed a memorable score that ranks among his best. THE GREAT ESCAPE was released by United Artists on July 4, 1963 to enthusiastic critical reviews, and box office receipts soared as audiences came to witness what is generally acknowledged as one of the best war pictures ever made, and a thrilling testament to the indomitable human spirit.

The film was shot entirely on location in Europe, with a complete camp resembling Stalag Luft III built near Munich, Germany. Exteriors for the escape sequences were shot in the Rhine Country and areas near the North Sea, and McQueen's motorcycle scenes were filmed in Fussen (on the Austrian border) and in the Alps. All interiors were filmed at the Bavaria Studio in Munich.

Hundreds of extras were recruited from a university in Munich, but to save time in the casting schedule, Sturges gave bit parts to grips, wardrobe personnel and his script clerk.

During the climactic motorcycle chase, Sturges allowed McQueen to ride (in disguise) as one of the pursuing German soldiers, so that in the final sequence, through the magic of editing, he's actually chasing himself.

Several cast members had been actual P.O.W.s during World War II. Donald Pleasence was held in a German camp (Stalag Luft I), Hannes Messemer in a Russian camp and Til Kiwe and Hans Reiser were prisoners of the Americans. James Clavell who co-wrote the screenplay, had been imprisoned in a Japanese P.O.W. camp during World War II, where his experiences formed the basis of his novel KING RAT.

Wallace Floody, a former prisoner-of-war at Stalag Luft III, was hired as the film's technical director. He gave his unqualified approval to the detailed sets, saying that Sturges and the crew achieved an "authenticity that was too real for comfort".

Charles Bronson, who portrayed the chief

tunneler, brought his own expertise to the set; he had been a

coal miner before turning to acting and gave director Sturges

advice on how to move the earth. Although McQueen did his

own motorcycle riding, there was one stunt he did not perform

for insurance reasons: the hair-raising 60-foot jump over

a fence. This was done by McQueen's friend Bud Ekins, who

was managing a Los Angeles-area motorcycle shop when recruited

for the stunt. McCallum remembered that during their spare

time, everyone worked on making the fake barbed wire into which

McQueen's character would crash his motorcycle.

The following information is from ESCAPE

ARTIST: THE LIFE AND FILMS OF JOHN STURGES by Glenn Lovell

(University of Wisconsin Press 2008)

The film was originally budgeted at $2.3

million, but script revisions, unseasonable weather (it snowed

on July 4) and McQueen, who eventually went AWOL, caused what

was to be a sixty-day production schedule to more than

double--at $30,000 a day, so the production eventually bloated

to $4 million.

Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster were sought for

the principal POWs, but their combined asking price of $1

million put them well beyond the budget. Dean Martin and

Frank Sinatra, George Hamilton, John Mills and Richard Harris

were also mentioned for the leads, with Harris actually cast as

Roger Bartlett, but filming ran long on THIS SPORTING LIFE, so

the role went to Richard Attenborough.

James Garner, cast as the Scrounger, had

scrounged for officers in Korea and acknowledged "there's a

little of me in the role."

Jud Taylor was promised the third American

character, Goff---provided he pay his own way to Germany.

Sturges: "I had the cast of a lifetime, plus my pick of the best actors in Germany."

The screenplay went through eleven drafts by at

least a half a dozen writers. William Roberts, Walter

Newman, W.R. Burnett and Nelson Gidding, a former POW, each took

a crack at adapting the book, but wound up "inventing things,"

according to Sturges, because they thought Brickhill's story was

too farfetched. Producer Mirisch: "The book was

the primary source for the escape, but we had to create

characters. That's where Jim [Clavell] came in."

Originally the film was to be shot in

Idyllwild, California with some German locations. But when

Reddish and Relyea flew to Munich to scout second-unit locations

(train stations, meadowlands, towns along the Rhine), they

telephoned Sturges to say how different Germany looked from

California. In addition, the Mirisch Company faced labor

problems with the Screen Extra Guild which would not allow their

members to be bussed farther than 300 miles from

Hollywood. Extras in Germany cost only $15 a day, so the

filming was relocated abroad.

Indoor scenes were shot outside Munich at the

Bavaria Film Studios in Geiselgasteig. The POW compound was

constructed nearby in a cleared pine forest. The Interior

Ministry permitted the American company to clear four hundred

trees---the saplings to be replanted elsewhere, the mature trees

to be replaced two-for-one.

The POW compound was what Sturges called a

"360-degree set" that could be photographed from any

angle. A reporter called it "the most depressingly

realistic POW camp you ever set eyes on." It helped

immeasurably, said the director, that some of the actual events

in the story "took place not ten miles from this studio."

The barracks interiors and a cross section of the tunnel, with

fat lamps and operational trolley, were built inside the massive

soundstages.

During his visits, technical advisor Wally

Floody was in such demand, he was passed from department to

department---"by appointment only." "You must be

getting something right," he told Sturges after squirming

out of the studio tunnel, "because I'm having terrible

nightmares." Donald Pleasence, a WWII veteran who

sat out the war in a Baltic POW camp, also had flashbacks.

"It was an exact reproduction of a prisoner-of-war camp, and

just as frightening," he said.

The cast arrived in early June. Coburn

and Bronson were in a Munich hotel. Steve and Neile

McQueen had a house in Deining. Garner and Sturges had

chalets in Munich. McCallum and wife Jill Ireland rented a

guesthouse on Lake Stamberg. McQueen, drawn to the

Autobahn by its unlimited speed limit, was perpetually

lost. The afternoon he was scheduled to check in, he

missed the studio exit by 150 miles. Throughout the shoot,

he would infuriate the local authorities by tearing to and from

the studio in his Mercedes 300SL convertible. Authorities

rigged a speed trap especially in his honor.

Because of a rumor the film was in trouble,

Sturges screened 45-minutes of dailies from the first six

weeks. Not much of McQueen had been shot (or even

scripted) at this point, and many of the cast thought the film

was destined to be a disastrous flop. McQueen was also

jealous of Garner's screen time and his "goddamn white

turtleneck".

Garner agrees, saying he and Jim Coburn

got with Steve "and went over the script, scene by

scene. We figured it out. Steve wanted to be the

hero---but he didn't want to do anything heroic."

Sturges: Steve was "groping around, ad-libbing, trying

to figure out how he could make the switch from loner to a

member of the 'X' team; I couldn't get Steve to realize that

that was his part, the loner. He kept getting upset

because he wasn't involved with the mechanism of the escape."

McQueen called Stan Kamen, his Hollywood agent,

who flew to Munich to calm his client. As soon as he left,

McQueen disappeared, saying, "I'm not coming back unless that

thing is fixed." Sturges shot around McQueen and

told Garner that Steve was out. The following week Steve

was back, agreeing to behave. Sturges contacted Ivan

Moffat, a war buddy of George Stevens, who had worked on SHANE

and GIANT and now lived in England. Moffat's

contributions, during a two-week stay, were small but

crucial. He wrote the scene in which Hilts tests a blind

spot between guard towers by tossing a baseball at the fence and

the exchange in which Bartlett and MacDonald con Hilts into

becoming their advance scout.

Much of the humorous July 4th celebration by

Hilts, Goff and Hendley, who buy up the camp's potatoes for

moonshine, was improvised, including their comic "Wow!"

when they taste the home brew. According to Neile: "Steve

couldn't get the timing right, and John [Sturges] stayed on

him until he came up with that scorched-throat sound."

The escape by train was done with a vintage

steam engine and two passenger cars purchased from a

junkyard. It was photographed live (no process shots) on

the busy Munich-Stuttgart run. The single-engine Bueker

181, a flimsy trainer purchased from a Belgium collector for

$250, used by Henley and Blythe in their escape, was piloted by

Relyea.

The Hilts motorcycle jump, actually done by

Steve's stunt double, Bud Ekins, was shot in a meadow outside

Fussen on the Austrian border. McQueen did do the rest of

his own motorcycle stunts. Sturges: "That's him

in beer-bottle goggles playing a German soldier chasing

himself."

As money started to run out, Sturges cut

numerous scenes, including the "mole" breakout by Hilts and

Ives, a cooler montage (Hilts eating, doing pushups, etc.),

Blythe coping with his blindness, Danny and Willie in a rowboat

narrowly avoiding capture by sentries.

The scene of Danny and Willie boarding a

Swedish freighter ran into trouble when the captain refused to

let Bronson and Leyton do it because he thought the film unit

was German. Falling snow obscured the filmmakers, and

Sturges yelled to Bronson and Leyton, "Get on the [ship's]

ladder! Kick the rowboat away! Climb up the

ladder!"

The rough cut ran more than five hours. Originally it was planned to release a 3 hour film as a special "roadshow" with intermission and reserved seating, but prime theatres were "illegally block-booked" by competing studios. Additional lost scenes included those between Hendley and Blythe, Hilts refueling his motorcycle and sampling Sedgwick's special escape rations, and Sedgwick trying the American's brew and finally opening his suitcase. Sturges: "It was funny stuff,. Sedgwick, who's Joe Organization, stops by a stream, opens the thing and in it he has food, wine, change of clothes, a compass, and a book. He starts nibbling the cheese, drinking the wine, reading the book. Got a big laugh. But it had to go. Length."

Sturges phoned Garner from the editing

room. Over lunch the next day, he said, "Jim, the two

best acting scenes in the picture are between you and

Pleasence. The only thing wrong is they're on the

cutting-room floor. I've got to stay with Steve on the

bike." (McQueen is onscreen more than anyone---43

minutes in total). Garner: "I thought it

was very classy of John to call me and tell me before I got to

the preview. I accepted it because of the way it was

presented. He was a very classy guy."

For his stirring tuba-and-woodwinds score,

Elmer Bernstein recycled a martial theme he had written at age

14. Bernstein: It was "jaunty,

nose-thumbing in character...adolescent rather than

adult and meant as a cheeky counterpoint to the foreground

heroics. Apart from that, it was simply a matter

of getting behind the action and McQueen's character."

It has become the official song of the English national soccer

team.

When the film was screened for United Artists,

they wanted it cut still further. So the scene where the

tailor (Robert Desmond) shows 'X' his new line of civilian

clothes made from blankets and uniforms was cut. Because

UA demanded hefty interest on the $1 million overage, Sturges

and Harold Mirisch went to Pacific National Bank for a

loan. The board agreed, provided they could see the

film. "They loved it, but couldn't understand how the

men got their civilian clothes. So back it went."

Often when shown on TV, this sequence is cut, however.

The world premiere was held in London at the

Odeon Leicester Square Theatre, preceded by an RAF benefit and

an afternoon screening for Floody and other surviving members of

Stalag Luft III, who gave the film a standing ovation.

Sturges was designated a "Friend of the Royal Air Force" by the

RAF at the London premiere. However, in 2006, camp

survivor B.A. James called the film "a load of rubbish; the

first part of the film wasn't bad, but the second half was

just Hollywood fantasy, an excuse for McQueen to ride his

motorbike. There was no motorbike. Nobody pinched

a plane either."

The film more than doubled its investment,

earning over $16 million. Since its release, THE GREAT

ESCAPE has steadily gained in stature as a pop-culture

touchstone. In 2001, it made AFI's list of 100 Most

Thrilling Movies at number 19. The film remains a cash cow

for distributor UA/MGM, which released a collector's edition DVD

to commemorate the 60th anniversary of D-Day.

YouTube: